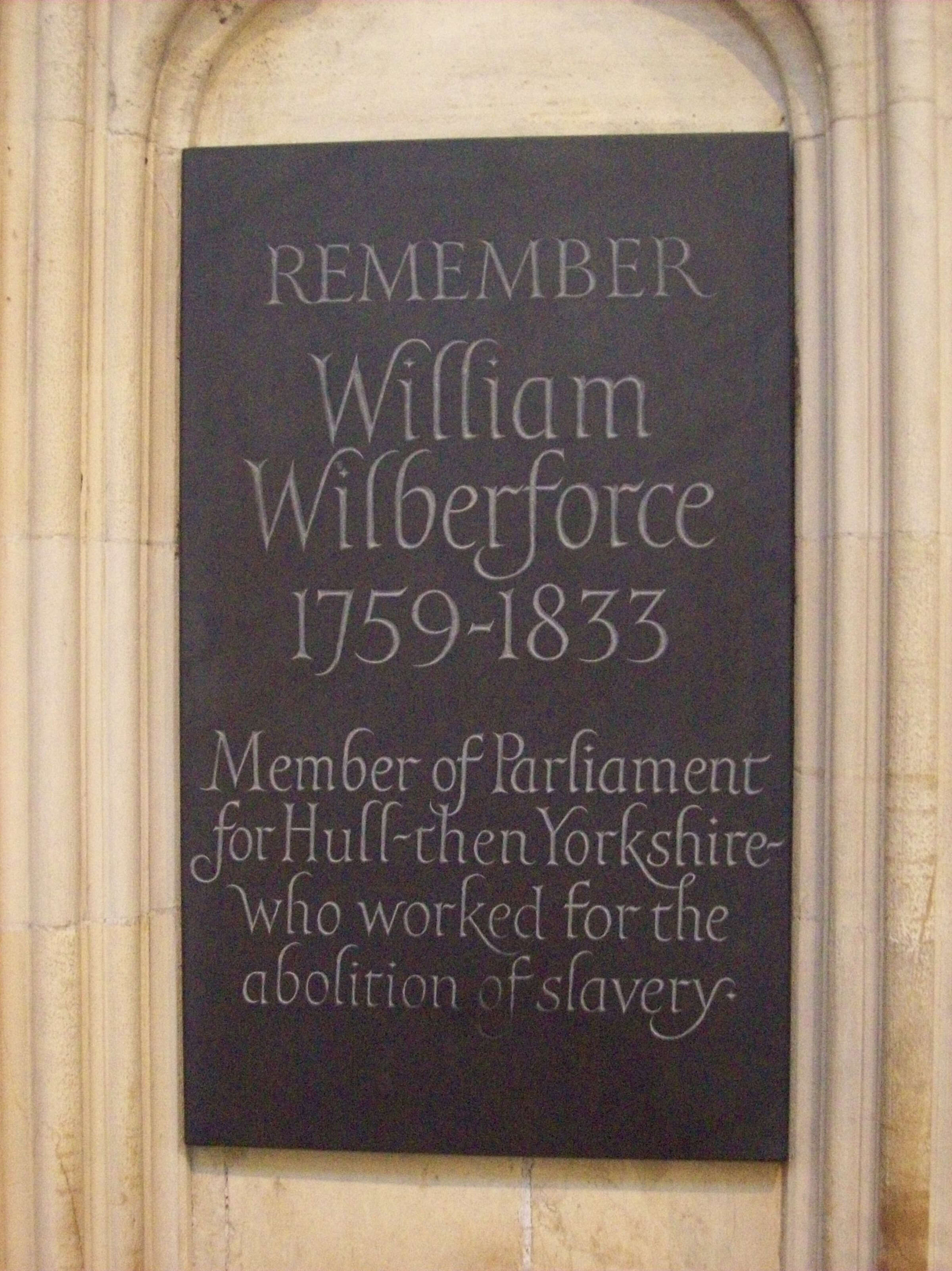

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce is one of the most significant figures in British politics. He was an MP in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, dedicating 45 years to the abolition of slavery and the slave trade. He was also a philanthropist and campaigned in other areas such as prison reform, medical aid for the poor, restrictions on child labour, education for the deaf and better working conditions in factories. He also helped to set up what became the RSPCA. William Wilberforce was the most high-profile member of the Clapham Sect – a group of Christian campaigners centred on an Anglican church in south London. One biographer, John Pollock, described him as ‘a man who changed his times’.

William Wilberforce is one of the most significant figures in British politics.

Early life

William Wilberforce was born in Hull in 1759, the only son of a wealthy merchant. At school his teacher made him stand on the desk to read his essays so that everyone could hear his eloquence. Wilberforce was 10 when his father died. His mother sent him to live with his aunt, Hannah. She was linked to the Methodist Church and brought Wilberforce up to follow this style of Christianity. But his mother, a more traditional Anglican, disapproved of such non-conformist influences and brought him home. At 17 Wilberforce went to Cambridge University and he became financially independent the following year. His wealth meant he would never need to work and this reduced his desire to study. He immersed himself in the social life, becoming a popular figure known for his wit, conversation and generosity. He made many friends, including William Pitt, the future Prime Minister.

Early parliamentary career

It was Pitt who persuaded Wilberforce to stand for parliament. He became MP for Hull in 1780, while still a student, aged just 21. Wilberforce stood as an Independent, which freed him from party political ties but he was an ally of Pitt. He attended parliament regularly and built a reputation as an orator. In 1784 Pitt won a big parliamentary majority and became Prime Minister; Wilberforce took the seat of Yorkshire. They remained close friends but Wilberforce was never offered a ministerial post.

Finding faith and a new purpose

Wilberforce’s spiritual life took a new direction when he went on a tour of Europe in 1784-5. He travelled with his mother, sister and Isaac Milner, the brother of his former head teacher, who was an evangelical Christian like his Aunt Hannah. Wilberforce’s faith was reignited: he began to get up early, pray and keep a spiritual journal. He turned his back on his previous lifestyle. He shut himself away from his friends for months, while he studied the Bible and religious books. He gave up dancing, theatre and society parties and decided to put his life to better use. He considered giving up parliament to become a priest. But John Newton, the Anglican clergyman best known for writing ‘Amazing Grace’, persuaded him to stay on and put his Christian faith into practice there. At that time Britain was one of several European countries which transported slaves from Africa to the Caribbean and America. At the peak of the trade, Britain was transporting 40,000 slaves a year, chained up on filthy, disease-ridden ships. Campaigning to stop the slave trade had begun in the early 1780s with the setting up of Quaker anti-slavery committees. But the protestors needed someone in parliament to drive through a change in the law. Wilberforce was encouraged by abolitionist campaigners such as Thomas Clarkson, Hannah More and Charles Middleton and by William Pitt to take the lead.

Continued below...

The fight against slavery

Wilberforce was driven into many other campaigns and causes by his Christian conscience.

Wilberforce, with the help of other abolitionists – notably Clarkson - spent two years researching the evils of the slave trade. In 1789, he gave a three-hour speech to parliament detailing its horrors and demanding an end to the trade. But there was a powerful slavery lobby in parliament. MPs decided to have their own inquiry before going any further. Wilberforce continued the research. He brought proposed legislation to the House of Commons in 1791 with more evidence but faced as much opposition. And the political backdrop was unhelpful: it was the aftermath of the French Revolution and there were slave revolts in the colonies. This combined to scare many MPs off abolition which had become associated with radical politics. The bill was defeated. But Wilberforce kept plugging away. In 1792 he introduced another bill. It was passed – but only after a minister had inserted the word “gradually” into it, making it meaningless. Undeterred, Wilberforce continued to introduce abolition bills throughout the decade, despite waning support. A change in political tactics in the early 1800s and an increase in the number of abolitionist MPs gave the campaign new momentum. Finally on 23 February 1807, MPs backed a bill to abolish the slave trade by 283 votes to 16. Wilberforce sat in tears as MPs paid tribute to his work. The passing of the Slave Trade Act was not the end. Wilberforce and his friends now campaigned to get the law enforced and to persuade other slaving nations such as France and Spain to abolish the trade. And there was a final step – the abolition of slavery itself. In 1823, Wilberforce published a book arguing for their emancipation and co-founded The Society for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery. But failing health prompted him to step down as an MP and hand over the leadership of the emancipation campaign. Then, in July 1833, three days before Wilberforce died, MPs voted through legislation which freed slaves throughout the British Empire. The Slavery Abolition Act became law in 1834. As a result, nearly 800,000 African slaves were set free.

Campaigning on other issues

Wilberforce was driven into many other campaigns and causes by his Christian conscience. He supported better conditions for factory workers and chimney sweeps. He opposed bull baiting and was a founder member of the RSPCA. He backed free schools, hospitals and medical dispensaries. He was also a founder of the Bible Society, and the Church Missionary Society. And he gave up to £3,000 a year to people in need – equivalent to £150,000 today. Wilberforce was a social conservative and campaigned against what he saw as a rising tide of immorality. This work was not always successful but supporters credit it with helping to shape public manners and stimulate a greater sense of social responsibility.

Mary Seacole

The Archbishop of Canterbury