OPINION - Transhumanism and being human

As a 7-year-old, I fell under the spell of Fame - the 1980s television series. It was largely based on the leg warmers and the theme tune. Presumably, like others, I danced round the living room with my sweatbands on and hairbrush in hand as a fake mic. The theme tune, a glorious piece of early 1980s discotheque rock, has Irene Cara declaring in the chorus “(Fame) I'm gonna live forever, I'm gonna learn how to fly (High)”. Surely a cry for immortality?

I think that there is something in every human being which makes us want to live forever!

Our human nature suggests we all have some kind of longing for eternity. The writer of Ecclesiastes, a book in the Old Testament, says that God has set eternity in our hearts. We want to live for ever. We want to be like God. The bible has a number of themes around becoming like God. The author of 2nd Peter writes that God, in Christ, has ‘given us his very great and precious promises, so that through them you may participate in the divine nature.’

In the incarnation of Jesus Christ we see the transformation of human nature into divine. We are to be co-heirs with Christ in the future reign of God. In Orthodox theology, ‘the human person is called into a development, evolution, from being the image of the triune God, to becoming a likeness of the Original Image. Orthodox theology names theosis or divinization. On her or his mission to this goal of perfection, as the prophet of creation, the human person is bringing along the whole creation to its refinement.’

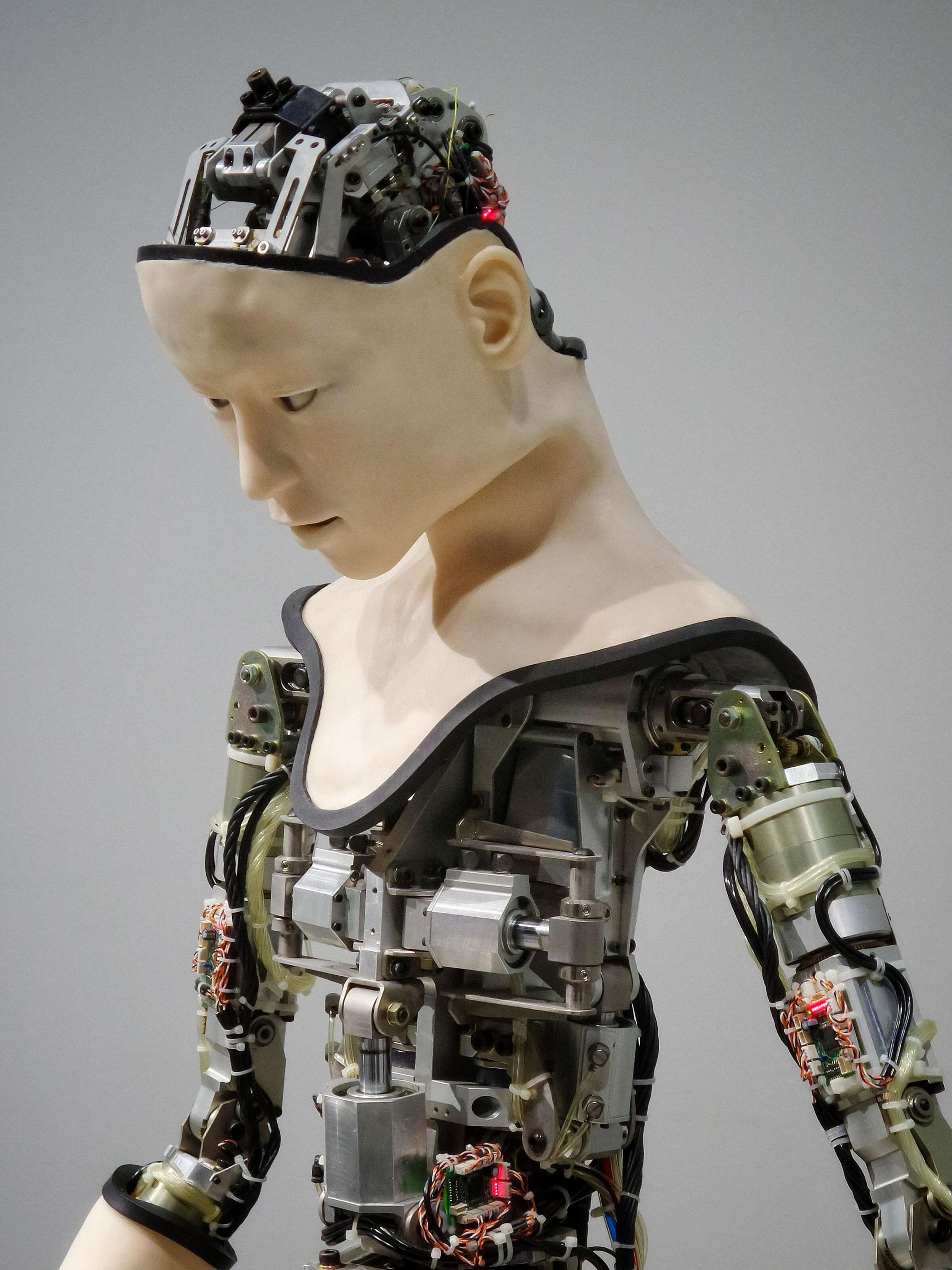

In a nutshell transhumanism is the belief that the human race can, with technological intervention advance beyond its physical and mental limitations.

So what is transhumanism? And why does it matter? In a nutshell transhumanism is the belief that the human race can, with technological intervention advance beyond its physical and mental limitations. Recently tech overlord Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, has poured millions into researching the potential for age reversal. It seems through the centuries we as human beings have been fascinated by the idea of eternal youth and breaking free from our physical limitations. The ideas in transhumanism are both laudable and concerning. It is also true that certain elements of transhumanism are becoming more common place and have benefits from a medical and human well-being perspective.

We know that technology is changing all the time and in many cases promising us lives which will be better. How we regard these technologies should never be an unreflective process. We should not simply consider technologies as benign tools for human self-actualisation. Transhumanism regards technology as a way of by-passing the limitations of the human condition. The Transhumanist Manifesto challenges the issue of human ageing and the finality of death by advocating three conditions. These conditions assert that ageing is a disease; augmentation and enhancement to the human body and brain are essential for survival, and that human life is not restricted to any one form or environment.

However, transhumanists are really products of the enlightenment era; they firmly believe in the idea of endless progress believing in individual autonomy and the possibility of transcending the limitations of tradition, superstition, and fear. Whilst at one point the promises of sophisticated body modification seemed some way off they are, and will be, increasing in availability. Whether implants into, or under, the skin, or more innovative implants into our brains linked with nanotechnologies, these push the boundaries around the ‘who’ of being human as they seek new forms of humanity. Transhumanists fundamentally believe that the merging of flesh and bone bodies with machines has the potential to create new ways of being human. The transhumanist manifesto moves out further from accepting ourselves as we are and towards a more complex process of physical deification. In the Bible there was a point in Genesis 11 where human beings came together to build a tower to reach to the heavens – they desired fame and power, yet God stopped them.

Continued below...

Christians have different ways of approaching and understanding transhumanism. Theologians like Karen O’Donnell, formerly from the Centre for Digital Theology in Durham, seem to approach these topics which apparent hope. Karen has positioned herself as a theological dreamer performing thought experiments. O’Donnell says quite frankly that she lays her cards on the table by arguing that imago Dei is not normative and set but performative. Since that is the case, she suggests that there is potential in the realm of transhumanism and AI to learn, grow and develop in ways which mirror human relationality. She asks, ‘if Artificial Intelligence is autonomous and can learn, as a new Christian does, to perform the image of God and seek it in the other in specific, concrete situations, then would such AI be in the image of God by virtue of performing the image? Could it be ‘saved’?’

Whilst we might recognise the excellent questions Karen asks as important, we may find them somewhat utopian in nature. I want to suggest three ways (although there are doubtless more) that transhumanism is potentially unhelpful and needs to be carefully weighed:

Firstly, if transhumanism collapses meaning into ‘efficiency’ then it can be seen as a commodifying movement. The theologian Elaine Graham says that ‘transhumanism exhibits a secular scepticism towards theologically grounded values.’ Indeed, transhumanism views the human being ultimately as a human body. The body has attributes which are merely commodities. The body may be upgraded as I upgrade my iPhone on my Tesco mobile contract. However, Christians believe that the body is not merely an instrument. Neither does transhumanism seem to give a clear account of human beings in relation to one another.

Secondly, transhumanism is essentially elitist. Any quick glance through the websites of biohackers and grinders and it becomes obvious that this is purely for those who can afford it. The rise of transhumanism has the potential to further extenuate the gross inequalities we see being played out globally. Upgrading is and will continue to be only accessible to a few – those with enormous wealth. Whatever future projections for more accessible and egalitarian options, it will be a technology clear totally unavailable to 99% of the global populations.

Thirdly and finally, transhumanism promises a false horizon of human invincibility and freedom from pain and suffering. Whether the dreams of Jeff Bezos to create some elixir of life and inhabit eternal youth are actually possible is secondary. Transhumanism is predicated on a fundamental misstep – deification is – the life of the age to come – a gift of God which cannot be realised through our own volition.

Being truly human is profoundly rooted in our physical limitations, idiosyncrasies, vulnerability, fragility and weakness. For all our longings to be freed in some way from those limitations it is living in, with and through them in our physical bodies, makes us who we are called to be. This is not to write off medical technological advances in ways which are mindful of the human person, but it does call us to live honestly with the fact we cannot ultimately avoid our frailties and finally our deaths.

‘Christianity’ says Rowan Williams, ‘has particular theological reason for valuing the local and material.’ Indeed the incarnation is absolutely vital to reflections on our own humanity. Jesus comes to us limited, time bound, and whilst his resurrection body gives us a taste of our bodies' eschatological transformation, it is a gift of God rather than for our own determination. We cannot engineer ourselves out of our ultimate vulnerability. John Swinton reminds us ‘who we truly are – is not a product of human possibilities but is, rather, something that is given to us and at the same time hidden from us in Christ.’ Pressing into understanding this truth is an important consideration for Christians assessing transhumanism and its potential benefits as well as pitfalls.

What is the purpose of life?

Life after death